Trusting identities in the digital atmosphere may be a cautious trail to walk on. For years, theorists have discussed the innate importance humans have to present identity in their everyday lives, and now with the digital world, this has been taken to the next level. Think about the days before technology, when only one’s first impression of someone would define them, not what or wasn’t posted on Instagram stories.

Instances like this pre-digital world were largely studied by Eric Goffman. He believed the world to be a theatrical performance, every day no matter who you’re with or where, one is tweaking their ‘self’ in order to please their surroundings. Scannell (2007) summarizes how aggressively Goffman viewed this change in self, “Thus what happens to individuals, on entering total institutions, is the systematic destruction of their former ‘civilian self.” Now obviously the question arises how does this, commonly known as ‘cynical’, theory relate to social media? Well as Goffman’s theories were published in the 1900’s, it’s almost like he was ahead of his time. While his conclusions may have been harsh for the intimate analysis of human interaction, they can be applied to digital world interactions. The social media world is built around aspects to change the perception of identity. The personalization of what is viewed is all directly controlled by the account holder, meaning Goffman’s infamous lines, “Front stage situations call for care in the projection of a managed self-performance” Scannell (2007,) are coming to life in a never-expected far more strong way.

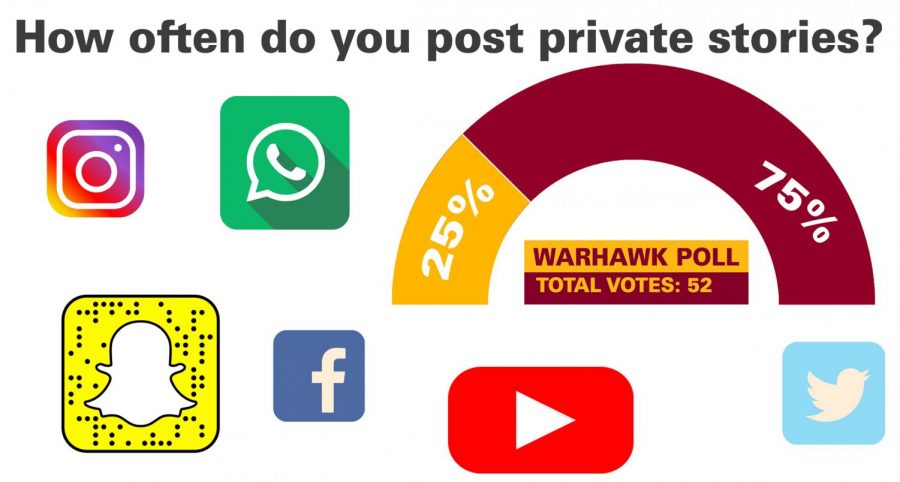

It is worth noting that there are several features enclosing this, one that is popular across all social platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat, is the idea of ‘close friends/private stories’. This is a story where the user can choose exactly who can and can’t see the posts, even though it is public. This is training users to choose who can perceive them in different ways, and showing a special ‘face’ for the selected audience. Goffman’s theory in his instance is spot on, and the more social media grows, the stronger his publishings feel like a prediction of the future. The next is the concept of ‘catfishing.’ Users care so much about how others perceive them on media, that they will completely alter their appearance and personality, an alter ego, yet claim that it is their own, to receive the deserted response from their audience. This issue of the perception of identity being skewed is no joke,” Since 2019, the average number of quarterly reports jumped from 3,131 in 2019 to 8,596 in 2022” Josh Koebert (2023.) Thousands of people are reported yearly creating a fictional persona to entice others into perceiving them in specific ways.

As seen, the construction of identity in the digital world has become a vital obsessive task for many users worldwide. Some may even say that the construction of identity on social media is the cause of heavy narcissism. When the worth of others is slowly put onto their digital identity, their social perception of them innately becomes very materialistic. Looking at physicalities more than who they really are. “The narcissism seems to be now displaced onto this new ideal ego, which, like the infantile ego, deems itself the possessor of all perfections” (Freud, [1914] 1984: 94.) I Believe the construction of identity in the digital world is a rough patch as the digital era progresses. As read above, More and more time and information is put into the digital self rather than the physical everyday life, resulting in a harsh reality of perception self-obsession.

Bibliography:

All About Cookies. (2023). Catfish Capitals: These Are the Places You’re Most Likely To Fall Victim to a Catfishing Scam. [online] Available at: https://allaboutcookies.org/catfishing-scams-by-state.

Scannell, P. (2007). Media and Communication. SAGE.

ENDO, P. (1998). Freud’s Psychoanalysis: Interpretation and Property. American Imago, [online] 55(4), pp.459–482. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26304601.