Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky co-authored the book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, revealing that ŌĆ£manufactured consentŌĆØ is essential to understanding the formation of opinions and the exercise of power in society. This theory explores how the media aligns public perception with the interests of the dominant power structure.

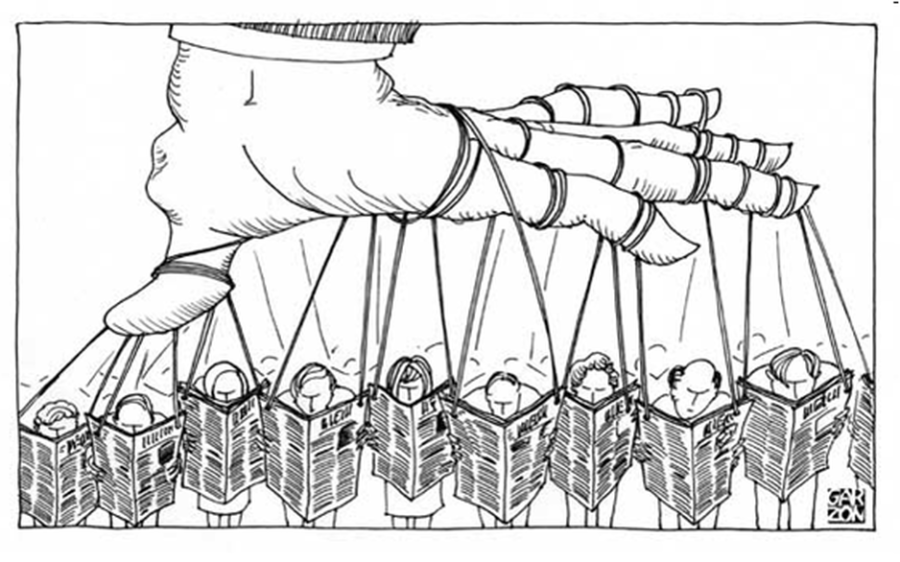

Manufacturing consent refers to using the media to influence and control public opinion in support of the agenda of political and economic elites. This process relies on systematic bias rather than overt coercion, and how the media reports things unconsciously affects our perceptions. It creates a framework in which dissenting opinions are marginalized, and the dominant narrative becomes the ŌĆ£naturalŌĆØ way to interpret events.

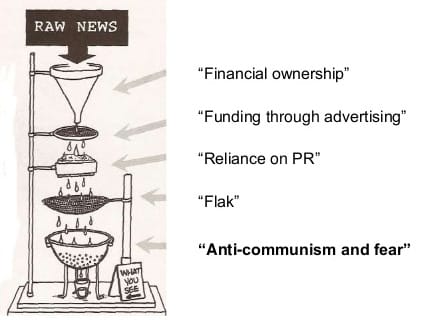

Herman and Chomsky developed the “propaganda model” to explain how media organizations perpetuate these biases. The model identifies five critical filters that information passes through before reaching the public:

- Ownership: Most mainstream media organizations are owned by large or wealthy corporations whose interests are aligned with the elite power structure. The media tend to avoid topics that are critical of their owners, and their priorities inevitably influence news and information reporting.

- Advertising: Advertising is the primary source of media revenue, which forces them to avoid publishing content that may offend advertisers or consumer groups, avoiding offending advertisers’ interests, thereby indirectly influencing news content.

- Sources: News organizations rely on government, corporate or public relations agency sources for information. Such “authoritative” sources have resource advantages that limit the ability of other media to challenge these sources critically.

- Criticism: Media content unfavourable to the elite or government may face legal threats and negative responses from them, resulting in retractions and financial losses.

- Counter-ideology: The media often portrays some countries or groups as imaginary enemies, playing on people’s fears and prejudices about (e.g., national security, terrorism) to justify the status quo.

The concept of manufactured consent is evident in all areas of life, with the media often presenting glorified, one-sided views of conflicts that align with government interests. Coverage of wars often portrays them as “just” or “necessary” while ignoring anti-war views.

Manufactured consent is more common in the entertainment industry, like the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard’s court battle. This high-profile legal dispute revolved around allegations of domestic abuse, defamation, and toxic relationship dynamics. The dispute began when Heard published an op-ed suggesting that she was a survivor of domestic violence. Although Depp was not named, they were in the process of divorcing at the time, and Depp believed that this defamed him, causing severe damage to his reputation and career.

The media’s portrayal of this case highlights how biased reporting can be. After the article was published, early coverage mostly sided with Amber Heard, portraying her as a victim of domestic violence, especially in the context of the #MeToo movement that believed survivors.

This narrative led to Amber attracting much support from women’s rights and anti-domestic violence activists, and some media outlets were quick to find Depp guilty. Depp began to fight back, revealing Amber’s violent behaviour through text messages, recordings and other evidence. Then, the media began to report extensively, changing his role from aggressor to victim. Platforms like TikTok and YouTube amplified this narrative, and memes and tags (#JusticeForJohnnyDepp) dominated the conversation. This influenced public opinion and portrayed Heard as a villain. Both parties’ careers suffered considerable impact and reputational damage after this incident.

This case embodies how media and public opinion are manipulated, reveals the interaction of power, economics and cultural narratives in shaping perceptions, and reminds us to be vigilant when questioning the stories we hear.

The media is not neutral, it can be a tool of power. Manufacturing consent allows us to understand the narrative intersection of power, media, and public perception. By recognizing the role of systemic bias, we can be vigilant against the manipulation of information and become more independent and sober participants.

Reference List:

Goodwin, J., Herman, E.S. and Chomsky, N. (1994) ŌĆśManufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass mediaŌĆÖ, Sociological forum, pp. 101ŌĆō111.

You started with Musk’s comments on Propaganda in today’s society, which is great. It directly brings up the theme of this blog, and it uses real-life examples, which is great. Then you discussed and explained Herman and Chomsky’s remarks. I saw your own understanding and brought in the model they proposed, which is really great. Finally, you added the impact that Depp and his wife suffered under the media’s public opinion some time ago, which greatly strengthened the persuasiveness of your argument. It’s really a great blog.

The article provides a comprehensive explanation of manufacturing consent, a theory that explains how media is a tool for elite power structures and systemic biases. It connects the theory to real world examples, such as the Jonny Depp and Amber Hears trial, demonstrating how media narratives are actively constructed and manipulated. However, it could benefit from a deeper exploration of counterforces to manufactured consent and discussing how independent media, social movements, and alternative narratives can challenge dominant media structures. This article does a great job of explaning a complex theory and relating it to real world issues.

This blog is a good analysis of the theory of ‘manufactured consent’, especially in the context of specific cases ranging from war coverage to entertainment news, and it vividly demonstrates how the media can manipulate public opinion through narrative. The use of Herman and Chomsky’s ‘propaganda model’ to explain the five filters of media bias is logical, and the case studies are compelling, such as the discussion of Johnny Depp and Ember Shields, which demonstrates how the media shape public perceptions through narrative framing. This cross-section of analysis, from serious news to entertainment hotspots, provides a deeper understanding of the pervasive nature of ‘manufactured consent’.

However, some of the examples in the article could have been explored in more depth, such as in the case of Depp and Shields, where it was mentioned that social media amplifies bias, but the specifics of how this affects different audience segments or the role of algorithmic recommendations in this regard were lacking. It would have been more complete to include more detail on how digital and traditional media work together or against each other. In addition, the section analysing ‘opposition creates consent’ could have included more practical advice, such as how to develop media literacy or identify bias in the news.

Overall, the blog is both theoretical and practical, but the balance between solutions and concrete analysis could be improved.