When I first heard the term — culture industry, I thought it simply meant the entertainment worldŌĆömovies, music, and media.

Hi! I am Jingyun. This week, I would like to share my opinions on the Culture Industry.

When it came to talk about culture industry, I had imagined concerts, TV shows, and blockbuster films, all the fun stuff we enjoyed in our free time. It sounded exciting, but I didnŌĆÖt realize there was a deeper meaning behind itŌĆösomething that goes beyond just watching or listening.

So what is culture industry?

The idea actually comes from critical theory, where Adorno and Horkheimer used it to describe how culture became industrialized under capitalism. Instead of art being a form of free expression, it started to look more like a factory productŌĆöstandardized, commercialized, and designed to make people consume without thinking too much.

How it developed’╝¤

This concept makes more sense when look at how society developed. Once peopleŌĆÖs basic needs were met, attention naturally shifted into emotional and cultural life. Culture became another kind of business. From film and radio to todayŌĆÖs digital media, creativity has been tied to economic systems. The internet just made it faster and biggerŌĆönow culture spreads instantly across borders, and we all become part of the global cultural market.

Personal experiences

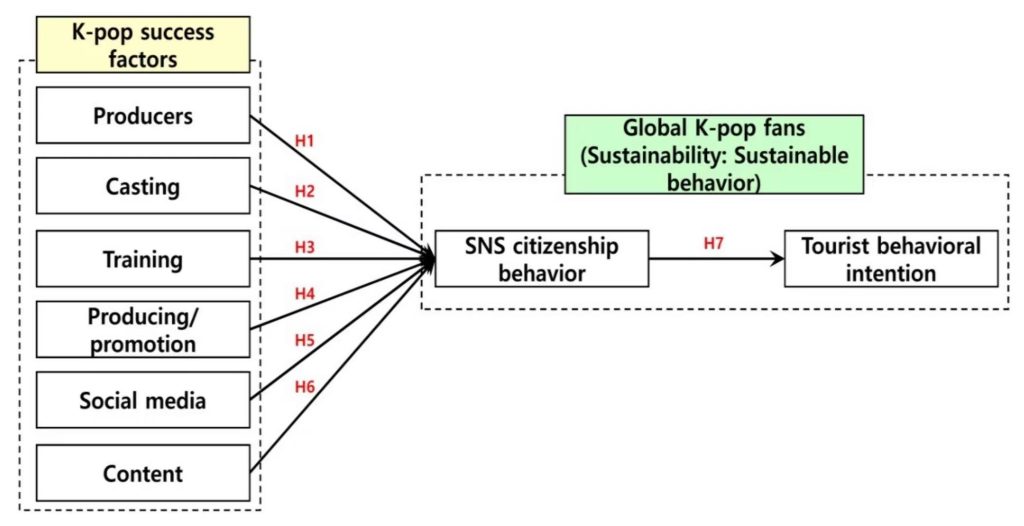

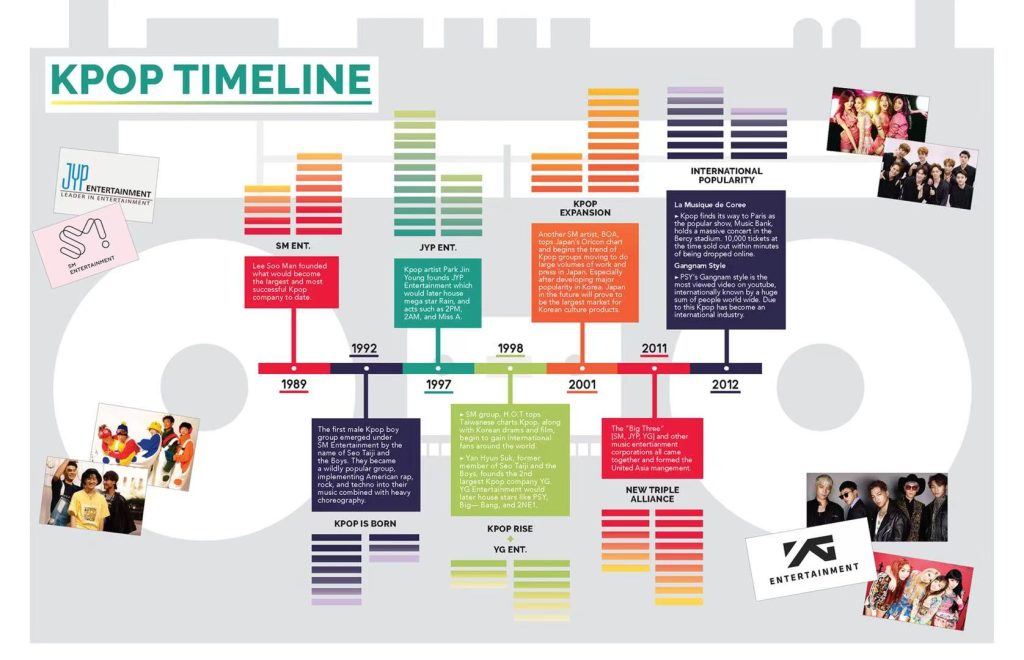

I really started to understand this when I got into K-pop. At first, I was just a fanŌĆöI loved the music, the aesthetics, the whole performance. But the more I learned, the more I noticed how organized everything was. The Korean cultural industry is incredibly complete, from training idols to marketing, distribution, and fan management. Every part of it works together perfectly, almost like an assembly line for emotions.

This is where the soft power of culture really shows. K-pop isnŌĆÖt just musicŌĆöit shapes how the world sees Korea, spreads language, fashion, and ideas, and connects fans across the globe. ItŌĆÖs a cultural export that builds influence without force.

ItŌĆÖs impressive, but also a bit strange. The creativity feels so carefully managed that sometimes it loses a sense of realness. Idols are often molded to fit specific images, and fans are encouraged to keep consuming. Groups can start to feel like products rather than artists. Still, I donŌĆÖt think itŌĆÖs entirely bad. The same system also builds community, gives people inspiration, and lets fans feel part of something bigger.

For me, the culture industry shows both sides of modern lifeŌĆöit can create beauty and connection, but it can also make everything feel controlled. Maybe what matters most is learning to enjoy culture consciously, without losing our ability to think and feel for ourselves.

That is all about my blog. See you next week.

I think that K-Pop is a really interesting example of culture as an industry! As you said, it is intended for entertainment and for emotional/personal connection, but it can also be so contrived and commercial. The carefully constructed and protected facades of celebrities like K-Pop idols, all of the business aspects behind them (managers, PR, agents, etc), and especially products like meet-and-greets or merchandise that are really just ways to profit off of devoted fans. I’d imagine there are a lot of people out there who are massive supporters of an artist/celebrity, who think they know exactly who they are or what they represent, when in reality they’re just the face of a character intended to take advantage of fans and their money. Then again, if you as the fan are getting worth and enjoyment out of whatever product or work, is that necessarily a bad thing? All in all, I agree that this is very representative of Horkheimer and Adorno’s idea that the culture industry is almost no more than a well-oiled capitalist machine. -Thalia Mott

Yes, I completely agree with your opinion. Standing from different perspectives, people may view the K-Pop industry in very different ways. For capitalists, itŌĆÖs indeed a highly effective marketing system that generates huge profits through a well-organized industrial chain. However, from the consumersŌĆÖ side, many fans are willing to spend money on what they love ŌĆö it gives them emotional satisfaction and a sense of belonging. Yet, over time, as the industry becomes more commercialized and repetitive, some fans might also start to feel tired or lose interest. Therefore, judging from the recent trends, the K-Pop industry seems to be experiencing a gradual decline, as audiences are becoming more aware of its commercial nature and seeking something more authentic.

–Jingyun

I agree with your opinion that the commercial model of K-pop has both pros and cons. While it does project an unrealistic ideal, it still provides emotional value to fans and gives them a sense of belonging to a community. Beyond the feeling of being controlled by capitalism (or the companies), I think fans of K-pop groups do have their own subjective initiative. They often reinterpret the work of their favourite idols by creating contents like “Stage Outfit Transformation” videos or organising charity events in an idol’s name. These actions are not controlled by entertainment companies. Although it might seem that fans are working for these companies without pay, they are not merely consuming but also producing. In other words, they are re-using the culture.

Yeah! YouŌĆÖre absolutely right. We can understand this process as a way for idols to maintain their exposure and continuously attract fansŌĆÖ attention, encouraging them to spend willingly. In the interaction between idols and fans, thereŌĆÖs not only a consumption relationship but also an important aspect of cultural production and transmission. Fans donŌĆÖt just consume what the industry creates ŌĆö through their participation, creativity, and emotional investment, they also contribute to spreading and reshaping the culture itself.