Fast fashion giants such as Shein, Zara and H&M operate on ultra-fast production cycles and extremely low-cost labor, generating vast amounts of textile waste. Yet despite ongoing controversies, these brands continue to attract massive numbers of consumers.Why havenŌĆÖt ethical concerns or environmental harm stopped people from buying fast fashion?Why does the industry grow even as criticism increases?

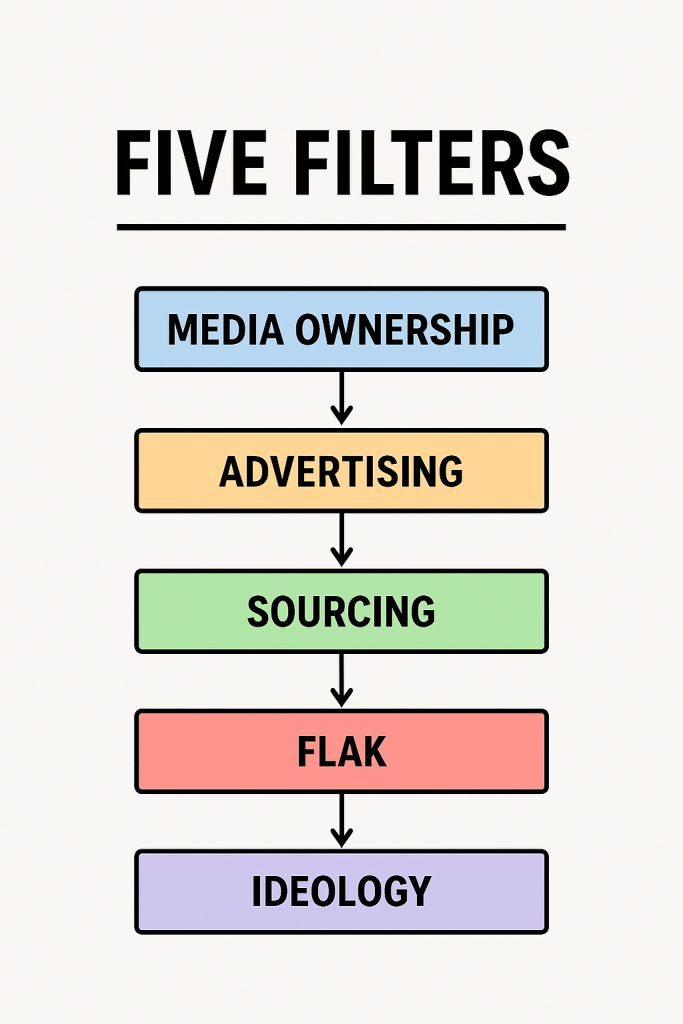

Herman and ChomskyŌĆÖs (1988) Manufacturing Consent theory offers a powerful explanation: fast fashion uses media structures to normalize, soften, and ultimately legitimize a harmful yet convenient model of consumption.

A quick different example can help you know easily.

1. Ownership: When big capital owns the media, criticism rarely survives

According to the first filter of the propaganda model media ownership major media outlets are controlled by large corporations. As a result, they have little incentive to publish content that could undermine their own business interests or those of major advertisers.

Fast fashion brands pour enormous budgets into Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube ads. Since platforms profit from this, critical reporting becomes rare. Even labor exploitation scandals or sweatshop expos├®s are often softened or buried unless they become impossible to ignore.

What consumers mostly see are:ŌĆ£New arrivals,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£outfit,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£haul videosŌĆØ not the ethical or environmental costs behind them.This aligns with research showing the severe environmental injustices embedded in fast-fashion production (Bick, Halsey & Ekenga, 2018).

2. Advertising Filter: Influencers as Perfect Vehicles for Fast-Fashion Messaging

Media outlets depend heavily on advertisers, giving advertisers indirect control over content. In the age of social media, influencer culture has become the ideal extension of this advertising filter.

Fast-fashion brands send influencers massive amounts of free clothing, turning their feeds into perpetual promotional campaigns. Collaborations create mutual dependence: influencers gain content and income, and brands gain exposure to millions of followers. In such a system, critical reporting simply has no place.

Research further shows that fast-fashion consumption often aligns with lower self-control and impulsive decision making, a psychology that influencer marketing strategically exploits (Huang, 2025).

3. Sourcing Filter: News Relying on Brand-Controlled Information

Many media outlets depend heavily on ready-made information from official or corporate sources. This reduces time, cost, and journalistic labour. As a result, news often repeats fast-fashion brandsŌĆÖ sustainability claims without scrutiny such as ŌĆ£eco-materialsŌĆØ or ŌĆ£green goalsŌĆØ despite the lack of independent investigation.

This creates a communication loop where consumers believe brandsŌĆÖ self-proclaimed environmental initiatives, even when these claims mask continued environmental harm (Bick, Halsey & Ekenga, 2018).

4. Flak Filter: Backlash Silencing Critical Voices

When influencers or journalists criticise fast-fashion brands especially on issues like labour exploitation.They often face coordinated backlash:Waves of hostile comments,Pressure from brand partners,Legal intimidation,Termination of sponsorships.

This environment teaches creators that criticism is risky, whereas silence is safe. The result is a media space where dissent is systematically suppressed.

5. Ideology Filter: The Cultural Logic That Makes Fast Fashion ŌĆ£Make SenseŌĆØ

Fast fashion thrives on a powerful cultural ideology: Everyone should stay trendy no matter the cost.

Media continuously reinforces ideas such as:Fashion as self-expression,Constant wardrobe updates, Sustainable brands being ŌĆ£too expensiveŌĆØ

Under this logic, ethical consideration becomes secondary. What matters is maintaining the illusion of affordable personal style.

Recent studies show that Gen ZŌĆÖs fashion behaviour is significantly shaped by digital communication that normalises fast-fashion consumption, even as sustainability awareness grows (Del Olmo Arriaga, Pretel-Jim├®nez & Ru├Łz-Vi├▒als, 2025).

Fast fashion is far more than a clothing industry it is a media driven system that uses ownership interests, influencer advertising, controlled sourcing, backlash mechanisms, and ideology to manufacture public consent. Consumers believe they are freely choosing what to buy, but their choices are shaped by a carefully designed media environment.

Through this multilayered filtering process, fast fashion normalizes environmental harm, labour exploitation, and hyper-consumption all while maintaining the appearance of harmless affordability.

A short video can help you review quickly.

Bick, R., Halsey, E. & Ekenga, C.C., 2018. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environmental Health, 17(1), p.68.

Del Olmo Arriaga, J.L., Pretel-Jim├®nez, M. & Ru├Łz-Vi├▒als, C., 2025. From fast fashion to shared sustainability: The role of digital communication and policy in Generation ZŌĆÖs consumption habits. Sustainability, 17(18), p.8382.

Herman, E.S. & Chomsky, N., 1988. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books.

Huang, Y., 2025. Fast fashion consumption signals low self-control. Journal of Consumer Research, advance online publication.

Such a great contemporary example of manufactured consent. Your post really made me think about how the filters are at work on us, even when we’re making what seem to be inconsequential decisions or spending. Similar to a prior post I saw about how “everyone knows climate change is a bad thing,” yet we don’t do much about it because the media coverage makes it seem like a smaller issue or out of our hands, this raises an interesting idea- “everyone knows fast fashion is a bad thing.” And yet these companies continue to thrive and expand? Everything you raised concerning social media like advertisements, brand deals, influencers, flak, etc. applies to Herman and Chomsky’s theory, but it also makes me think about how class and financial systems play into the phenomenon. Fast fashion is cheap and accessible, as opposed to more ethically or sustainably produced options. This only builds on the manufactured consent working against the general public, while also making us the “bad guys” for letting fast fashion persist. -Thalia

Your interpretation of how fast fashion shapes public perception through Manufacturing Consent was very clear. I especially agree with your point that carefully curated media content can make harmful production practices look normal or even harmless. What impressed me most was your insight into how the media structure of fast fashion not only suppresses criticism but also reshapes what we recognise as a ŌĆ£problemŌĆØ. When unsustainable production is reframed as ŌĆ£affordable trendsŌĆØ or ŌĆ£personal expressionŌĆØ, environmental damage and labour exploitation become positioned as acceptable effects. The shaping of this meaning feels like a deeper form of manufactured consent.