Studying Stuart HallŌĆÖs Encoding/Decoding made me rethink how I look at the cultural world around me, especially the things I usually scroll past without much thought. When I first came across HallŌĆÖs idea that media producers encode certain meanings and audiences interpret them through their own experiences, and then read Hua HsuŌĆÖs explanation of this in his New Yorker piece, it suddenly felt directly relevant to the kind of content I see every day (Hall, 2006). That connection is also why I ended up choosing the KardashianŌĆōJenner family for this blog. They appear everywhere in pop culture, and their brands show up on my feed constantly, so they felt like a fitting example because they are so closely tied to what is trending right now. I never really thought of SKIMS or Kylie Cosmetics as cultural texts before; to me they always looked like trendy products and clever marketing. But seeing how differently people respond to them made me realise they are actually a perfect case for thinking about how meaning is produced and interpreted in contemporary media. As Hua Hsu notes in The New Yorker, HallŌĆÖs work encourages us to take popular culture seriously because these negotiations of meaning often happen most visibly within it.

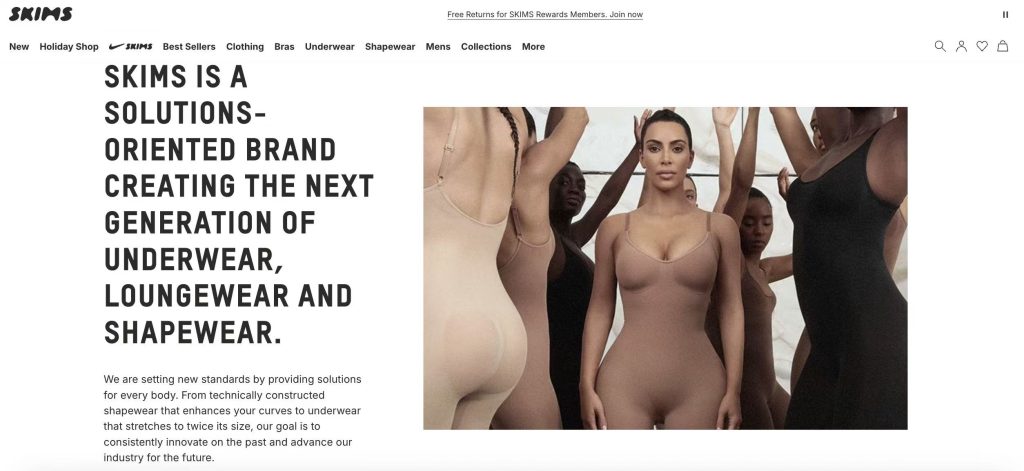

SKIMS presents itself as a body-positive label created for ŌĆ£every body,ŌĆØ and this narrative is clearly encoded into its campaigns. The visuals emphasise inclusivity, comfort and modern femininity. But when I talk to people around me, I immediately see HallŌĆÖs three reading positions at work. Some take a dominant reading, fully accepting the message of empowerment and seeing SKIMS as a refreshing alternative to older shapewear brands. Others respond in a negotiated way: they like the products but remain sceptical of the commercial motivations behind the brandŌĆÖs claim of inclusivity. And then there is the oppositional reading, where people feel that selling shapewear goes against the idea of body positivity altogether. The brand encodes one message, but audiences decode it through their own values, insecurities and experiences.

Kylie Cosmetics works through a slightly different mechanism. Much of its influence comes from social media creators who showcase the products in casual and relatable ways. These short videos encode a lifestyle where beauty seems accessible, fun and effortless. Again, I see the three reading positions clearly. A dominant reading treats these videos as authentic and creative. A negotiated reading acknowledges their appeal but also recognises the commercial collaborations behind them. An oppositional reading questions how ŌĆ£realŌĆØ the content is, especially given filters, editing and the algorithmic visibility that shapes what we see. Even when the message looks natural and spontaneous, the decoding continues to shift depending on the viewer and the context.

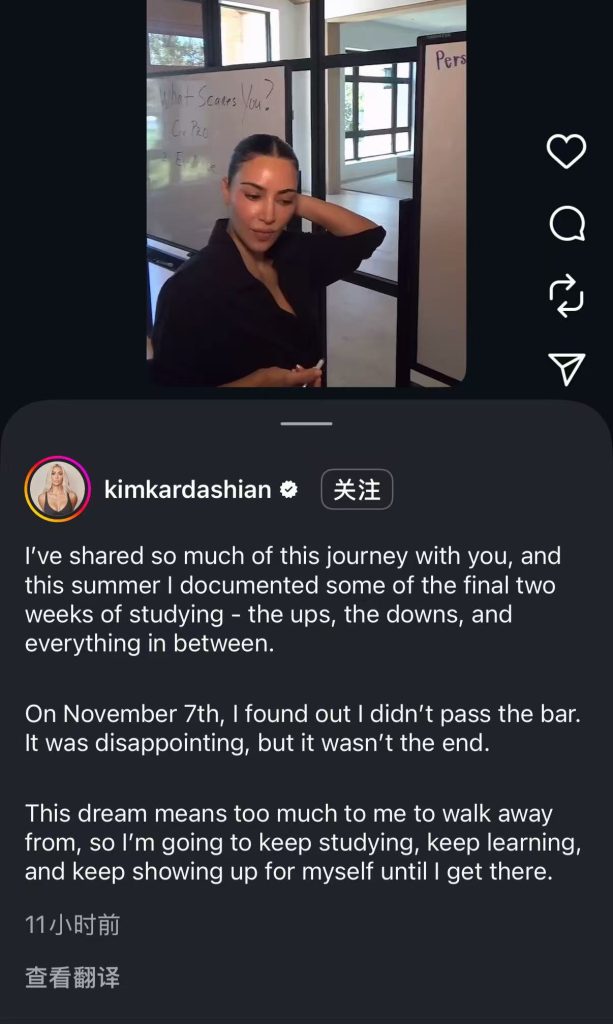

The most revealing example for me is a recent post from a Kardashian family member talking about failing a law exam. The encoded meaning was one of vulnerability, determination and hard work. My own first response was a dominant reading, because it felt inspiring to see someone so famous openly discuss an academic setback. But the comments showed a negotiated reading, where many people supported her effort while also pointing out that her journey is shaped by privileges most people do not have. Others took an oppositional reading, interpreting the post as another method of maintaining relatability and managing a public persona. Even a moment that appears personal becomes a space where meaning is contested.

Looking at brands like SKIMS and Kylie Cosmetics made me think again about what Stuart Hall was trying to explain. These brands work very hard to create a clear story about confidence, inclusivity and accessible beauty, yet the way people respond shows how unstable those stories really are. A message never arrives untouched. It passes through peopleŌĆÖs hopes, insecurities and personal histories, which is why the same campaign can feel empowering to one person and uncomfortable to another. As I reflected on my own reactions, I realised that the moments when I feel drawn to these brands, or when I start questioning their intentions, usually come from my own background and the ideas about beauty I grew up with. I used to assume I was just neutrally ŌĆ£seeingŌĆØ advertisements, but now I can tell that I am constantly shaping the meaning as I read it. Becoming aware of this made me look at everyday media differently. It reminded me that decoding is always personal, and that my own experiences quietly guide the things I think I understand.

Reference List

Hall, S. (2006) ŌĆśEncoding/decodingŌĆÖ, in Hall, S., Hobson, D., Lowe, A. and Willis, P. (eds.) Culture, Media, Language. London: Routledge, pp. 163ŌĆō173.

Hsu, H. (2017) ŌĆśStuart Hall and the rise of cultural studiesŌĆÖ, The New Yorker, 17 July. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/stuart-hall-and-the-rise-of-cultural-studies (Accessed: 17 November 2025).

Kylie Cosmetics (n.d.) Kylie Cosmetics by Kylie Jenner. Available at: https://kyliecosmetics.com/ (Accessed: 17 November 2025).

SKIMS (n.d.) SKIMS: Solutions for Every Body. Available at: https://skims.com/en-gb (Accessed: 17 November 2025).

Through reading your blog, I can clearly understand how decoding depends heavily on individual experiences, values and social background. As you pointed out, education, upbringing and personal beliefs all influence the way people read media texts ŌĆö which means there is never a single ŌĆ£correctŌĆØ interpretation. What I find particularly interesting is how a well-designed campaign encodes multiple layers of meaning. It doesnŌĆÖt simply promote a product; it also invites wider social attention ŌĆö sometimes even shaping public discourse. Perhaps this is its deeper purpose. From a critical perspective, I started to wonder: when we decode these messages, are we actually becoming a part of their strategy? In a way, our reactions ŌĆö whether dominant, negotiated or oppositional ŌĆö may still serve as resources for the brandŌĆÖs visibility and public influence. Your blog really made me reflect on this ŌĆö especially on the possibility of developing a more critical mindset when facing highly strategic media texts. I think this is what we should continue exploring: how to decode without being quietly absorbed into the process of encoding itself.

When I read this assignment blog, I resonated with it a lotŌĆöbefore, I only saw SKIMS and Kylie Cosmetics as “influencer brands” too, and this analysis made me realize for the first time that the “kind of liking but also kind of doubting” feeling I get when seeing their ads is exactly what Hall calls “negotiated reading”.

YouŌĆÖve combined your tangled feelings about the brands with the theory so naturally, especially when you wrote about the different opinions you and your friends had about Kylie Cosmetics. It immediately made the point of “the individuality of decoding” feel so vivid. After reading it, I also started thinking about how many unspoken “oppositional readings” are hidden in my usual judgments of these brands.

You spoke very well! Your examples of SKIMS and Kylie Cosmetics are very relevant to reality, making Hall’s three reading methods suddenly become extremely specific. Indeed, some people fully accepted it, some were half-believing and half-doubting, and some completely rejected it. I myself often waver between negotiation and opposition, especially when seeing those natural and unfiltered beauty videos, I always feel that something is not quite natural. After reading this blog, there is a feeling of “oh, it’s not that I’m passively consuming something, but actively participating in the production of meaning.” Such reflection is very solid and very life-like.