I once believed that technology was neutral, but learning about algorithmic bias has changed my view. Algorithms are not objective, they can reinforce social inequalities, quietly aggravate discrimination based on gender, race, skin colour, and behaviour.

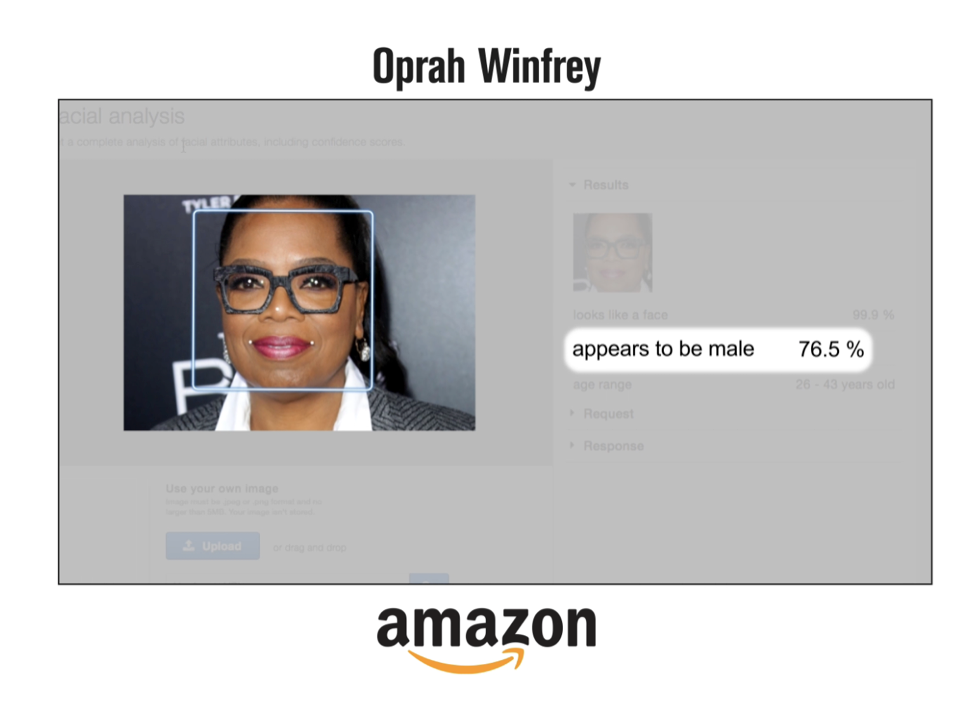

First, algorithmic bias stems from data bias. Friedman (1996) pointed out that all technical systems carry social values because data comes from human society, and society itself is unequal. The study by Buolamwini and Gebru (2018) showed that commercial facial recognition systems achieved 99% accuracy for white men but only 65% for black women. This is not because machines choose to discriminate. There were few samples of black women in the training data, so the model could not make accurate judgements. The machine only reinforced the bias already present in society.

*image from: https://time.com/5520558/artificial-intelligence-racial-gender-bias/

Second, selective coding by technology companies is another key source of bias. Hall (1980) reminded us that the media encodes values from the outset, leaving audiences hard to be aware of the underlying ideology. Algorithmic recommendation functions as such a hidden power. Noble (2018) further argued that algorithms are not only mathematical logic. They are strategic choices made by platforms based on commercial interests. In 2025, the French regulator found that MetaŌĆÖs job advertising algorithm showed mechanic roles more often to men and childcare roles more often to women, which created indirect gender discrimination. This was not an accident. It was a valuable choice made by the system in deciding who becomes visible.

*image from: https://en.acatech.de/allgemein/the-future-council-of-the-federal-chancellor-discusses-impulses-for-germany-as-an-innovation-hub/

Third, algorithmic bias arises from the ways social inequality is reproduced and exacerbated. OŌĆÖNeil (2017) emphasised that the danger of algorithms lies not in the errors themselves but in the way these errors grow under automation and scale. A typical example is the COMPAS risk assessment model used in the United States. ProPublica (Angwin et al., 2016) found that the system often marked black people as high risk while white people were more often marked as low risk. In this vicious cycle, the police increased their patrols in black communities, and the data then showed a higher crime rate among black people. Thus, the algorithm model believed that these communities were more dangerous. Ultimately, the algorithm turned these judgements into objective data and made social bias look like scientific truth.

*screenshot from: https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing

Overall, the answer to ŌĆ£why do algorithms become biasedŌĆØ is not in technology but in social structures. Algorithms are not independent intelligence. They are a re-encoding of human data, decisions, and values. As technology is applied to commercial optimisation or content distribution, the underlying bias intensifies. Understanding algorithmic bias requires examining how technology and power interact: who designs the algorithms, who benefits from their bias, and who bears the costs.

To reduce algorithmic bias, we need more transparent data sources, stricter model checks and more diverse training data. What an algorithm becomes depends on the values we put into it and whether we are willing to question it. Avoiding algorithmic bias is, at its core, about avoiding bias in our real life.

References:

Angwin, J., Larson, J., Mattu, S. and Kirchner, L. (2016) Machine Bias. ProPublica. Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing (Accessed: 29 November 2025).

Buolamwini, J. and Gebru, T. (2018) ŌĆśGender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classificationŌĆÖ, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 81, pp. 1ŌĆō15. Available at: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v81/buolamwini18a.html (Accessed: 29 November 2025).

Featured image (2020) Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/recode/2020/2/18/21121286/algorithms-bias-discrimination-facial-recognition-transparency (Accessed: 29 November 2025).

Friedman, B. (1996) ŌĆśValue-sensitive designŌĆÖ, Interactions, 3(6), pp. 17ŌĆō23. Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/242485.242493 (Accessed: 29 November 2025).

Hall, S. (1980) ŌĆśEncoding/decodingŌĆÖ, in Hall, S. et al. (eds) Culture, Media, Language. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128ŌĆō138.

Noble, S.U. (2018) Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press.

OŌĆÖNeil, C. (2017) Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Crown.

The Guardian (2025) ŌĆśFacebook job ads algorithm is sexist, French equality watchdog rulesŌĆÖ, The Guardian, 5 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/05/facebook-job-ads-algorithm-is-sexist-french-equality-watchdog-rules (Accessed: 29 November 2025).

This is a great analysis of algorithmic bias, what causes it and how to combat it. I would be interested to know what strategies media consumers can use to be aware of and combat bias in their own algorithms. I agree that it’s important to change the way we train and create algorithms to truly combat bias, but I wonder if there are ways that people on the ground level (like me) can try to be aware of the way my algorithms affect my own bias. I definitely think awareness and getting information and media from a wide variety of perspectives play an important role.