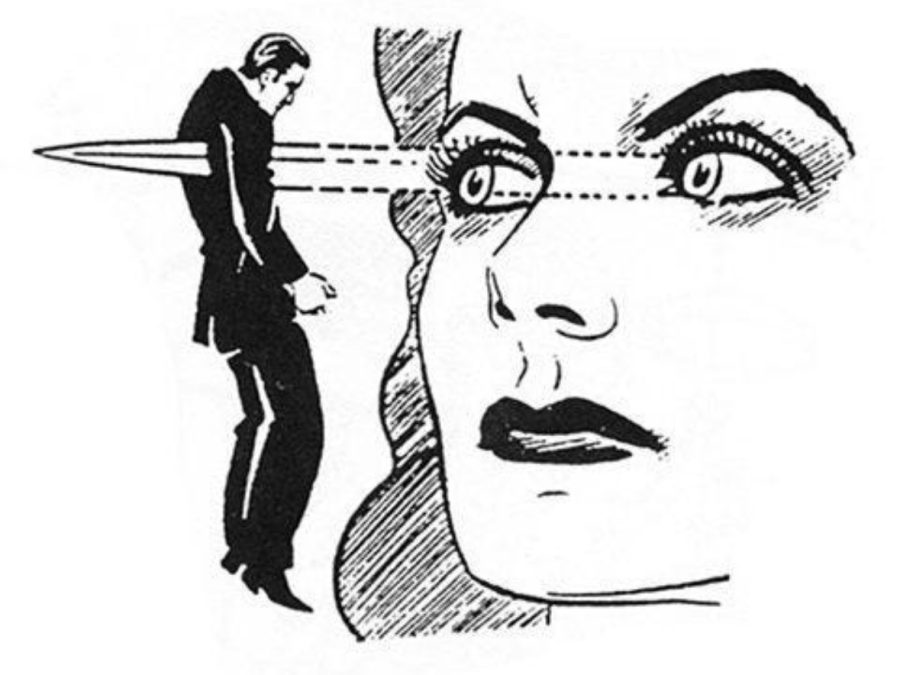

We often think “looking” is just accidental eye contact, but in cultural narratives, it’s one of the most invisible forms of power.On social media, it shows up as: being viewed, liked, boosted by the algorithm. It feels like being appreciated, but is actually aesthetic discipline ,only those who fit certain desires and frameworks get visibility. And this framework often comes from male centered power structures: The Male Gaze.

The gaze operates on three levels:The camera favors male desire. Narratives revolve around men. Audiences are trained to see male perspectives as universal.

The term was coined by film theorist Laura Mulvey, describing how cultural systems default to a “male desire” perspective, turning women from subjects with agency into objects to be consumed.(Mulvey, 1975).

Women become something to be looked at, not someone with their own desires and complexity.

The Male Gaze on Social Media

Women posting selfies seem free, but if they want visibility, they must follow what platforms reward.Rosalind Gill calls this the “postfeminist sensibility,” where women are encouraged to present themselves as confidently attractive while still conforming to deeply gendered expectations (Gill, 2007).

To get recommended by the platform and gain traffic, you have to fit the aesthetic preferences dictated by the platform’s algorithm. Yet behind these algorithmic aesthetic preferences lies the manifestation of the patriarchal power structure.Brooke Duffy’s research on female online creators shows the same pattern: platforms subtly punish women who don’t match preferred aesthetics, framing conformity as “best practice” (Duffy, 2017).

This is just male gaze logic updated for the digital age.

The Male Gaze in Film

Film has long trained viewers to see women in limited ways. Many female characters exist not for themselves but to support a male hero’s journey , her pain becomes his growth.

Visual culture scholar Gillian Rose explains that images don’t just reflect culture; they actively shape how we learn to look (Rose, 2016).This is why scenes like Megan Fox’s in Transformers feel so familiar: the camera slowly scans her waist, hips, chest, fragmenting her body into consumable symbols. She becomes an assemblage of “hotness,” not a character with agency.

The Male Gaze in Real Life

This gaze doesn’t only live on screens—it shapes daily expectations.

Girls are raised to be gentle, agreeable, and non-disruptive.

But when a woman finally recognizes her own ambition and moves with intention, she is often labeled too aggressive,”“too much,”“too dominant.”Yet men showing the exact same traits are praised for being confident and driven. Women can improve, but you can’t become too strong.

Across platforms, films, and everyday life, one pattern repeats Women are watched far more often than they are understood.

The problem is not that people look at women, but that someone else defines how women should be seen,

someone else controls the visual language around them.Resisting the male gaze means returning to female subjectivity not just being looked at, but being able to look back and writing yourself into the world.

Reference List

Duffy, B.E. (2017) Not Getting Paid to Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gill, R. (2007) ‘Postfeminist media culture: Elements of a sensibility’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(2), pp. 147–166.

Mulvey, L. (1975) ‘Visual pleasure and narrative cinema’, Screen, 16(3), pp. 6–18.

Rose, G. (2016) Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. 4th edn. London: SAGE.

You wrote very well, connecting the male gaze from film theory all the way to social media, algorithms and everyday gender expectations, with a very clear main thread. What you said about women often being placed in the position of “being looked at” in cultural narratives, and that the real issue is not the act of looking itself, but who has the power to decide how to be looked at, really touched me. The article successfully pointed out how this visual power constantly updates in different media, from classic film shots to platform algorithms, all influencing how women understand and present themselves. Overall, it emphasizes that regaining subjectivity means allowing women to write their own images and desires.

This breakdown of the male gaze across social media, film, and daily life is so sharp—especially how it’s evolved into algorithmic ‘aesthetic discipline’ online. The part about women being labeled ‘too much’ for ambition (while men get praised for the same) hits way too close to home. Resisting this isn’t just about ‘not being watched’; it’s about taking back the right to define how we’re seen. Such a thoughtful, necessary read.

You‚Äôve built a strong point between classic theory and contemporary culture. What stands out is how you show the male gaze not just as a film theory, but as something that still organises how we learn to look and to be looked at. I appreciate how you integrated multiple scholars’ takes on the theory to show the different layers that are incorporated. I especially like how you frame the oppositional gaze as an active practice rather than just analyzing it. Overall, your post does a great job showing why the gaze is still relevant and matters now just as much as when Mulvey first wrote about it. You balance explanation with critique, and you encourage readers to reflect on their viewing habits. Great job!