ŌĆ£Culture IndustryŌĆØ as a concept was developed in 1944, by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in their work ŌĆśDialectic of Enlightenment.ŌĆÖ Arguing that the culture industry tends to commodify culture and transform it into products for mass consumption as it is a ŌĆśstigma of capitalismŌĆÖ (Adorno, T.W, Bernstein, J.M., 2020). Emphasizing the homogenization of culture and how it shapes the public perception. Serving the commercial interests and being packaged and sold for profit rather than being in its true individual expression or creation.

BBC

Transfermarkt

GymNation

Ronaldo is not only a famous footballer; he is a global brand. His lifestyle, skills and persona are commodified and marketed to the global audience. Connected to Adorno and HorkheimerŌĆÖs ideology, individual athletes or artists are transformed into a commodity. RonaldoŌĆÖs image over the years has been used to sell a range of products, extending from sports gear to luxury, to appeal to a larger demographic. His multiple endorsements with brands (Nike, luxury watches, the CR7 clothing line) demonstrate how his own talent was repurposed to fit in as a broader commercial narrative.

Adorno and Horkheimer had this one criticism, which was the standardization of content within the ŌĆ£culture industry.ŌĆØ RonaldoŌĆÖs narrative is standardized and built around themes of greatness, success and individualism, aligning with capitalist ideals. His personal brand of triumph over adversity and continued dominance in football connects to the formulaic and predictable narratives seen in other pop culture areas. His personal story is marketed to make it seem easily consumable, stripping away the complexity of his life and career. His position in the cultural industry being used as a symbol people admire or aspire to be impacts how others define themselves.

The New York Times

British GQ

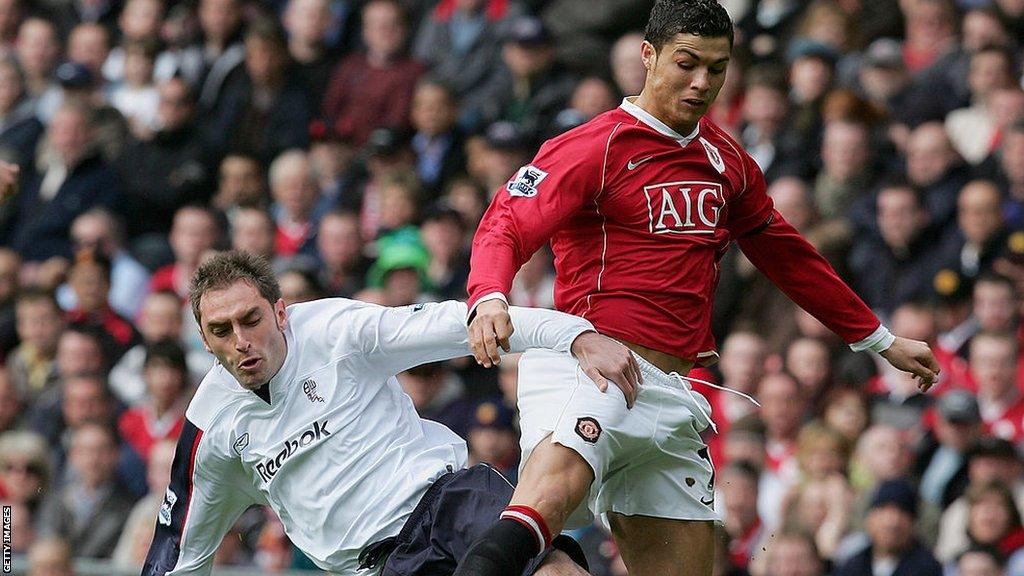

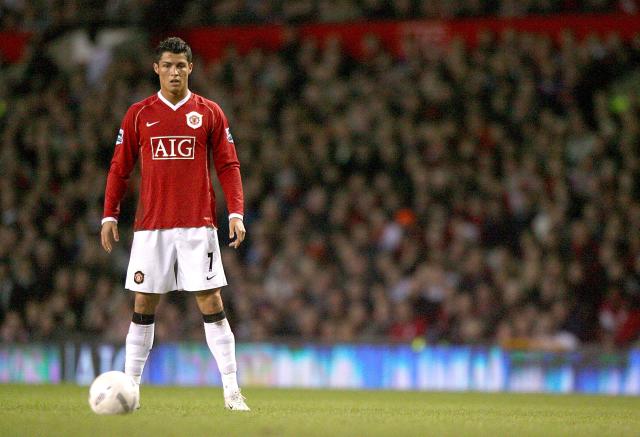

Cristiano Ronaldo, Manchester Untited (Photo by Nick Potts – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images)

The culture industry thrives on reaching a vast audience, and RonaldoŌĆÖs appeal is truly international. Being an accessible figure for millions, whether it is through advertisements or the selling of football kits. It relates with the culture industryŌĆÖs strategy of establishing globally relatable products, making them appealing and satisfactory to the audience. Ronaldo is often treated more as a product than a human. There is the constant need to produce content about him. Ranging from his personal life, training sessions or goals, to keep the commercial machine running. ŌĆśAmusement under late capitalism is the prolongation of workŌĆÖ (Horkheimer, M., Adorno, 2002). Ronaldo becomes a part of the commercial cycle, keeping him in a system of production, as seen from his transfer deals that are high profile, such as Al Nassr. His success isnŌĆÖt drawn just from him but also from the profitability of the media, club and advertisers, whom all profit from the ŌĆśproductŌĆÖ, which is Ronaldo.

RonaldoŌĆÖs overwhelming presence in the global media might reduce football to another substance in consumerism. Instead of the audience focusing on the beauty of football, their attention can shift to RonaldoŌĆÖs personal brand instead. As his involvement in marketing campaigns highlights the intersection of sports and capitalist enterprise, that could cause a distraction from the game. RonaldoŌĆÖs career and public image are exemplary of how entertainment, identity and sports are intertwined in contemporary culture.

References:

Horkheimer, M., Adorno, T.W. and Noeri, G., 2002. Dialectic of enlightenment. Stanford University Press.

Adorno, T.W. and Bernstein, J.M., 2020. The culture industry: Selected essays on mass culture. Routledge.

This blog does a great job of connecting Adorno and HorkheimerŌĆÖs ŌĆ£culture industryŌĆØ theory to RonaldoŌĆÖs role as a global brand. The analysis of how his image and talent have been commodified, aligning with capitalist ideals of success and individualism, really hits the mark. The post also effectively highlights how his carefully crafted persona, with themes of greatness and dominance, makes him a perfect example of how the culture industry shapes public perception through predictable narratives. It’s insightful to consider how RonaldoŌĆÖs branding reduces his identity to a consumable product, echoing the way mass culture standardizes content for profit.

While the commercial aspects are well-covered, there might be more to explore about RonaldoŌĆÖs own agency in this process. Is he just a product of the culture industry, or does he also shape his brand consciously, leveraging the culture industry to expand his influence? Additionally, it would be interesting to discuss how audiences engage with RonaldoŌĆÖs imageŌĆödo they view him solely as a brand, or is there still room for appreciation of his raw talent and personality? Including these perspectives could make the analysis even more rounded and provide a deeper look at the complex relationship between personal identity and commodification