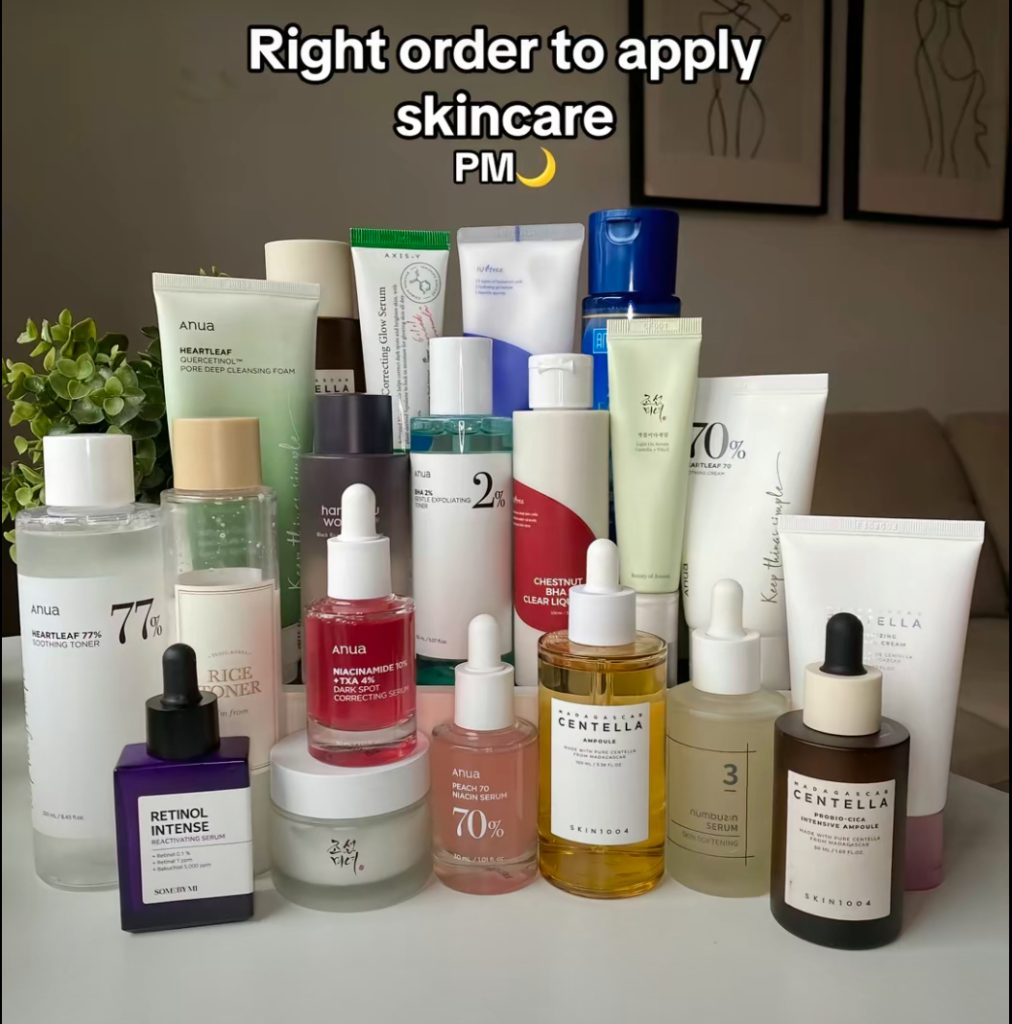

WeŌĆÖve all been there ŌĆō scrolling through a ŌĆ£Get Ready With MeŌĆØ (GRWM) video, watching someone dab on serums, massage creams, and layer moisturizers like theyŌĆÖre crafting a masterpiece. And before you know it, youŌĆÖre convinced that your skin might need the same 10-step routine just to make it through the day. But if we step back, this phenomenon isnŌĆÖt just about beauty tips; itŌĆÖs part of a bigger system, what Adorno and Horkheimer called the ŌĆ£culture industryŌĆØ, a world where even skincare is commodified to keep us perpetually consuming.

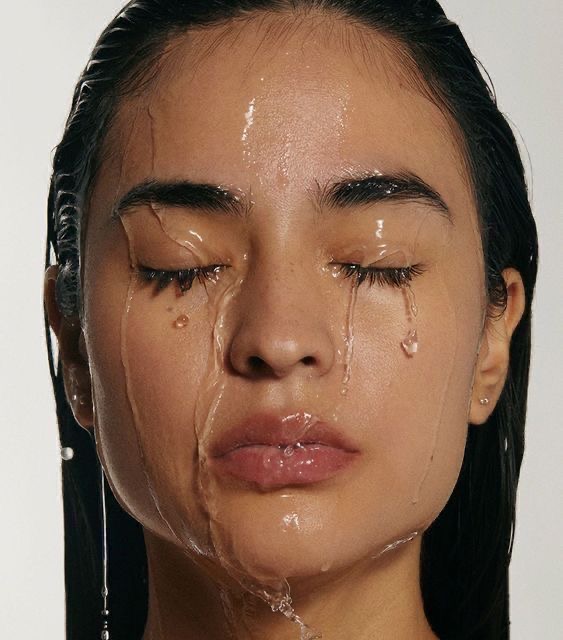

The culture industry, as they saw it, was a well-oiled machine that manufactured wants, directing people toward things they didnŌĆÖt necessarily need but had come to desire. Skincare and beauty brands have perfected this formula, convincing us that glowing skin or that coveted ŌĆ£glass skinŌĆØ look is only achievable through a ritual of endless products. This marketing strategy doesnŌĆÖt just target adults; it increasingly reaches younger audiences, with colorful packaging and playful branding designed to attract kids and tweens. Social media and GRWM videos feed us these routines daily, making it feel as if a few minutes with cleanser, moisturizer, and sunscreen arenŌĆÖt enough. Instead, itŌĆÖs a full production, with each product promising just a little more radiance or smoothness, all packaged with calming music and gentle application that make it seem like *self-care* rather than simply selling.

The beauty industry thrives on the creation of desire, convincing us that we need more to be enough.

Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women (1991)

ItŌĆÖs genius, really ŌĆō weŌĆÖre drawn in by the idea of self-improvement, thinking weŌĆÖre enhancing our lives. But Adorno and Horkheimer would probably argue that this ritualized consumption masks a deeper reality: by following the trend, weŌĆÖre encouraged to buy more products to feel fulfilled, even as that sense of satisfaction proves elusive. For instance, a new serum may flood our feeds, boasting the ability to reduce wrinkles, enhance radiance, or even turn back the clock on aging. WeŌĆÖre told that incorporating this single product into our routine will be the key to achieving the flawless skin we desire. Yet, as soon as we add that serum to our collection, the marketing machine rolls out the next ŌĆ£must-haveŌĆØ item, whether itŌĆÖs a trendy face mask or a night cream infused. This constant influx of products keeps us in a state of perpetual longing and dissatisfaction, as we chase after the illusion of beauty rather than truly embracing our skin as it is. All of this keeps us in the endless loop of consumption, where fulfillment remains just out of reach, perpetuating the cycle of desire that the culture industry has crafted.

So, as we dive into these routines, itŌĆÖs worth asking ourselves: do we really need all these steps? Or are we swept up in a cycle thatŌĆÖs not as much about skincare as it is about the lure of the culture industry, wrapped up in a rose-scented face cream?

Reference List

Horkheimer, M. and Adorno, T. (1972). Dialect of enlightenment.

N.Y.: Herder & Herder.Lawlor, S. (2019). A Three-Step Skincare Regime: Stripping Back Complicated Routines. [online] Glamour UK. Available at: https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/three-step-skincare-routine [Accessed 18 Oct. 2024]

Mccracken, G.D. (1988). Culture and consumption : new approaches to the symbolic character of consumer goods and activities. Bloomington, Ind. Indiana Univ.

Press.Wolf, N. (1991). The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women. London: Vintage Classic.

Sydney Schaffer (TikTok , 2024)

The 10 Step Trap

Hi there! I really like your perspective of combining the 10-step skincare approach with Adorno and Horkheimer’s theory of the “culture industry”, which reveals how the skincare industry creates “demand” through consumer behaviour. “The 10 Steps to Skin Care I have some new perspectives that might further the discussion.

Your reference to social media and beauty brands keeping people consuming through multi-step skincare reminds me of the ‘symbolic value’ of skincare products. As McCracken (1988) points out in Culture and Consumption, consumer goods are not just objects, but also contain our identity with self and society. Here, skincare products have gone beyond their functionality and have become a symbol of ‘fine living’. It is through the shaping of this ‘symbolic value’ that the culture industry may further consolidate consumer behaviour.

In addition, I particularly agree with your reference to the cultural industry’s influence on the younger demographic through the promotion of complex skincare procedures. For teenagers, the popularity of skincare and beauty content on social media can shape their understanding of “beauty” and even have a negative impact on a psychological level. However, I wondered if teenagers’ feedback on social media content is in turn shaping the culture industry. For example, as teens tend to seek out personalised, creative content, could this prompt brands to make changes in their advertising and marketing, creating a two-way cycle of influence? If so, how do you see the possibility of a two-way influence, where the ‘one-way shaping’ of the cultural industry may be differentiated by social media platforms?