The core of media theory – media shaping information – reveals the reason why today’s media is completely different from the past. What we receive is not only the content itself, but also these communication tools themselves redefining our way of thinking, communicating and behaviour. Here’s how the theory is applied to the platforms we use every day:

Short video:the dominance of ŌĆ£instant interactionŌĆØ

TikTok’s 15-60-second duration limit and algorithm-driven “recommended page for you” are not simple design choices, they are structural characteristics that determine user behaviour. This medium promotes fast editing, emotional hooks and fragmented views, and cultivates “fast-food” attention rather than deep concentration. A 20-minute climate change documentary is difficult to compete with a 30-second melting ice short video with popular music. This is not because the content is not important, but because TikTok’s design logic prioritises instant response rather than delicate expression. This is not a matter of content, but the medium is triggering the continuous stimulation that we desire.

From TikTok

Social media’╝Üblurring the boundaries between “public” and “private”

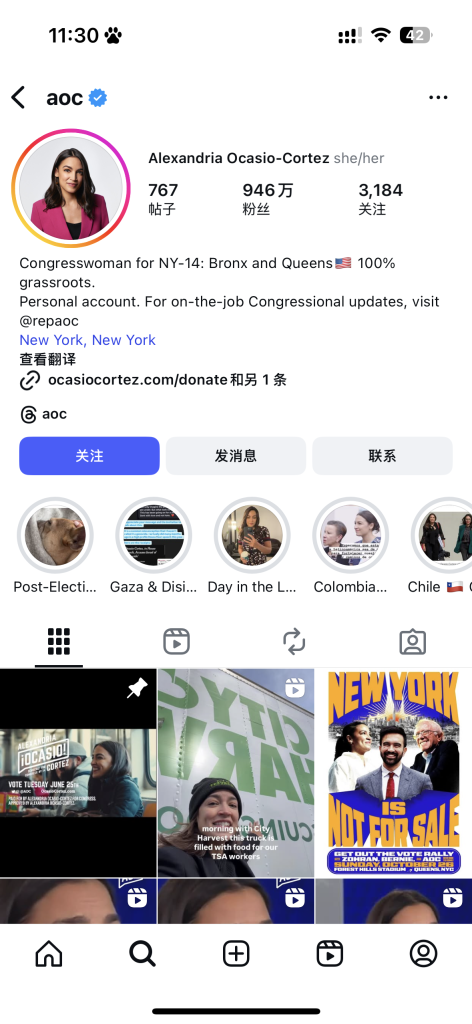

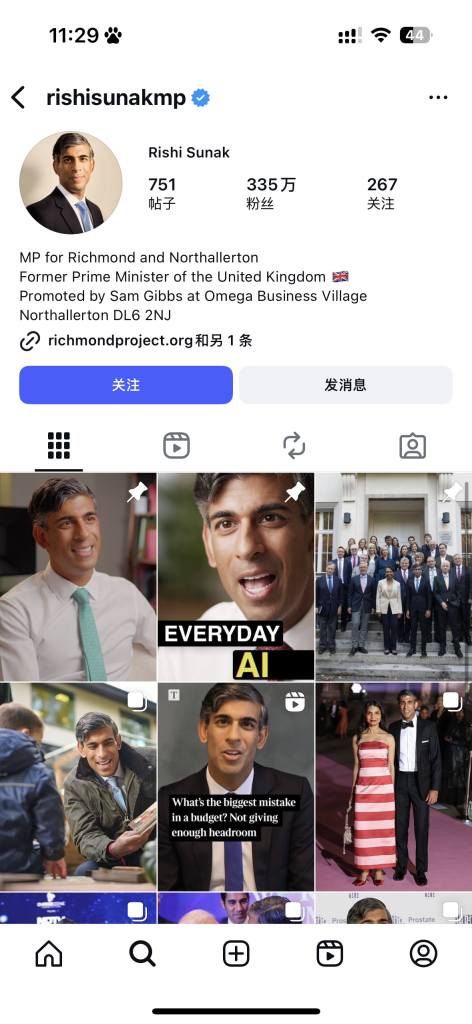

Joshua Melowitz’s research explains why it seems common to share family dinner photos or political hot comments nowadays. Traditional media used to strictly distinguish between “front desk” (public image) and “backstage” (private life), but platforms such as Instagram have broken this boundary. Publishing “daily vlogs” will turn private moments into public content, and replying to politicians’ tweets can allow ordinary people to enter the once elite-only realm. This transformation driven by media interaction redefines the connotation of “public life”.

Rishi Sunak: British Prime Minister, he will share their life and common values with his wife Akshata Murty on Instagram. For example, they once published an emotional post detailing their common hobbies and views on life, with photos of their love.

Algorithm push: “information cocoon” becomes the norm

Facebook, YouTube and other platforms use algorithms to filter content, and this feature has given rise to an information cocoon. If you watch a partisan video, the algorithm will push more similar content – not because the creator is biased, but the core goal of the media is to retain users. This biased automation rooted in platform design undermines the shared public discourse.

From YouTube

Conclusion

The value of media theory lies in letting us jump out of the single judgement of “content superiority and inferiority” and see the profound impact of the structural characteristics of communication tools on behaviour and culture: the duration limit of short videos reshapes the attention pattern, the interactivity of social media blurs the boundaries between public and private, and the underlying logic of the algorithm intensifies cognitive solidification. In today’s accelerated technological iteration, understanding the core logic of “media is shaping power” can help us use various platforms more soberly – not only using its convenience to connect the world, but also actively avoiding the limitations brought by its design defects, and becoming more rational media users and information consumers.

Reference list

Eisenstein, E. L. (1979). The printing press as an agent of change: Communications and cultural transformations in early-modern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Livingstone, S. (2009). Children and the internet: Great expectations, greater fears. Polity Press.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill.

Meyrowitz, J. (1985). No sense of place: The impact of electronic media on social behavior. Oxford University Press.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press.

Postman, N. (1985). Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. Viking Penguin.

This post accurately points out how short-video structures like TikTok shape attention and behavior. But I have a question: Does emphasizing “the medium is the shaping force” underestimate users’ interpretation and contextualized use? For instance, when political figures like AOC use Instagram, it’s not just one-way broadcasting but also in building intimacy and authenticity – this might be subtly reshaping the medium’s own logic. So, is this shaping force one-way, or is there some kind of dialectical interaction between medium design and user practice?

I enjoyed reading your take on using the medium theory. I think you make an interesting point on TikTok’s design for promoting “fast-food attention.” Nowadays, a quick and interactive TikTok video can quickly capture a person’s attention and create lasting effects. Sitting through a 30-minute-long documentary doesn’t give the same lasting impression to someone, as humans tend to lack patience. My question about this is, do you think that all media content is intentionally created to communicate the medium’s purpose? Or does it have different priorities for how the public interprets the content?