Encoding and Decoding: Navigating Meaning in Daily Life and Social Media

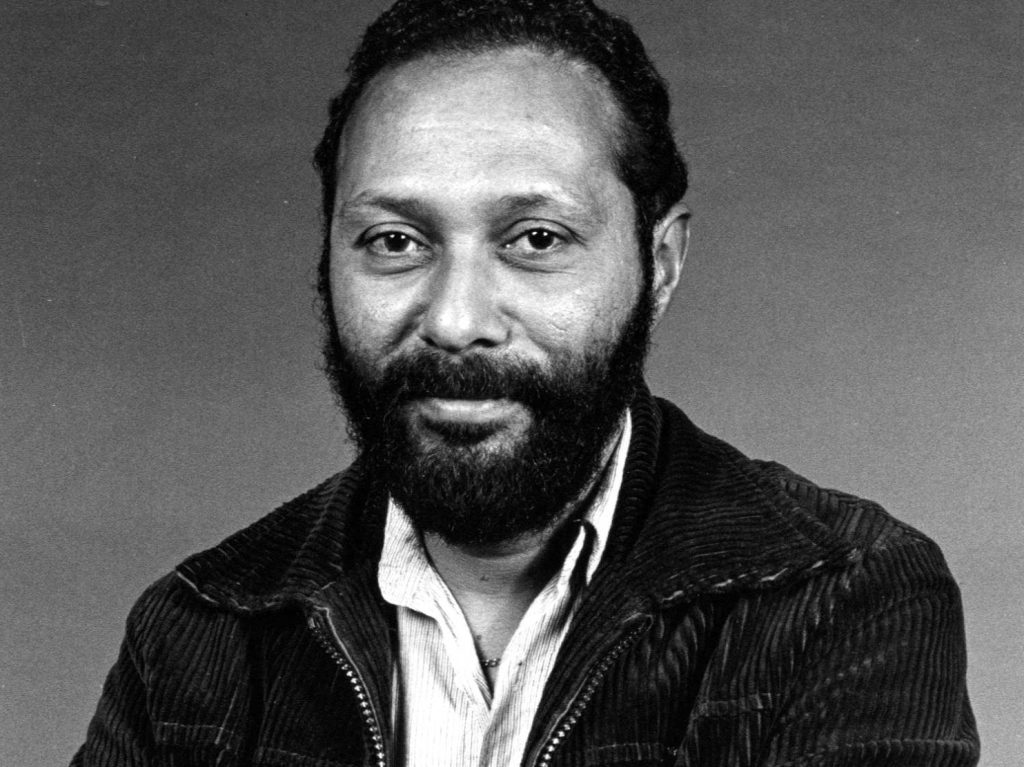

Coined by Stuart Hall in 1973, the encoding-decoding theory redefines communication as a dynamic, interactive process rather than a one-way transfer of information. Encoding refers to the act of transforming ideas into transmittable symbolsŌĆöwords, images, gestures, or soundsŌĆöshaped by the senderŌĆÖs cultural background, intentions, and context. Decoding, by contrast, is the receiverŌĆÖs interpretation of these symbols, equally influenced by their own experiences, values, and social position. Hall identified three decoding stances: dominant (aligning with the senderŌĆÖs intent), negotiated (partially accepting and reinterpreting), and oppositional (rejecting the intended meaning entirely). This framework illuminates why miscommunication is common and how meaning is co-constructed in interactions.

In daily life, encoding and decoding unfold in mundane yet profound ways. A parentŌĆÖs reminder to ŌĆ£wear a jacketŌĆØ encodes care and concern, but a teenager might decode it as an infringement on freedom (oppositional decoding). A colleagueŌĆÖs casual ŌĆ£we should catch upŌĆØ could encode genuine friendship (dominant) or a polite brush-off (negotiated), depending on the listenerŌĆÖs relationship with them. Even emojisŌĆösimple encoding toolsŌĆöare prone to decoding gaps: a smile might signal warmth to one person but insincerity to another, highlighting how context and familiarity shape interpretation.

Nowadays, social media amplifies and transforms this dynamic, blurring the line between encoders and decoders. Users are both creators and interpreters, engaging in ŌĆ£circular encodingŌĆØ where content is constantly reused and redefined. For instance, a short video of rural life encoded by a blogger to showcase simplicity may be decoded by urban viewers as an escape from stress, then re-encoded through remixes to promote mental health. This chain reaction exceeds traditional mediaŌĆÖs one-way model, turning audiences into active participants in meaning-making.

Social media also exposes the theoryŌĆÖs core insights through algorithmic dynamics and cultural clashes. Platform algorithms act as invisible encoders, curating content based on user behavior to create ŌĆ£information cocoonsŌĆØŌĆöa form of systematic encoding that steers audiences toward specific decoding patterns. Meanwhile, cross-cultural content often sparks decoding dissonance: an international brandŌĆÖs ad encoding individualism may be negotiated by East Asian audiences, who appreciate the product but question its emphasis on personal gain.

Moreover, social mediaŌĆÖs real-time feedback loops refine the encoding process. A beauty influencer might adjust their videoŌĆÖs tone (encoding) after viewers comment that their tips feel ŌĆ£condescendingŌĆØ (oppositional decoding). Similarly, public figures often clarify statements after fans or critics decode unintended meanings, turning negotiation into a public practice.

In essence, encoding and decoding theory reveals that meaning is never fixedŌĆöit is a dialogue between intent and interpretation. On social media, this dialogue becomes more democratic, chaotic, and influential than ever, reminding us that every post, comment, or share is a dance of symbols, shaped by who we are and what we bring to the conversation. Understanding this dynamic helps us navigate miscommunication, respect diverse perspectives, and engage more thoughtfully in the digital world.

Hello, your blog post has made me realize once again that although we are constantly “encoding” and “decoding” information every day, most of the time we are not even aware that we are being subtly influenced by algorithms, cultural backgrounds, and even emotional preferences. Your article emphasizes the diversity of interpreting meanings, which I fully agree with; but I think what is more alarming is that in social media, this diversity does not occur freely but is quietly shaped by the platforms through “information cocoons”. We think we are active decoders, but in fact, many times we are just passive products of the platforms’ sophisticated algorithms. Perhaps the greatest significance of understanding the encoding/decoding theory is to remind us that it is easy to see the information, but it is truly difficult to see the power structure behind it.

This interpretation is so vivid! The combination of coding/decoding theory with daily dialogue and social media is wonderful – it turns out that parents urge them to wear coats, and colleagues say “dinner appointment” is the scene of coding and decoding ¤śé

The paragraph “Users are both coders and decoders” on social media is too poking! Now watching short videos, the same stalk can be played with 800 meanings, which is the magic of circular coding ~ But the algorithm is also very heart-wrenching as an “invisible coder”: our interpretation preferences have long been quietly framed?

Now I want to think more about the news and the content – after all, every symbol is a “dance of intention and interpretation”~