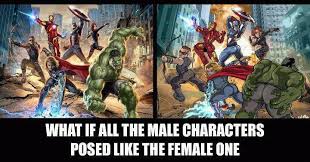

The┬Āidea┬Āof the┬Āmale gaze┬Āhas been around since Laura Mulvey wrote about it in the 1970s, but┬Āthe concept still feels very relevant today.┬ĀBasically, the male gaze explains how┬Āmedia┬Āoften shows women through a heterosexual manŌĆÖs point of view.┬ĀInstead of being full characters, women┬Āare filmed┬Āor photographed┬Ālike┬Āobjects to┬Ālook┬Āat.┬ĀThis┬Āmakes┬Āthe viewer┬Ātake on┬Āthe same point of view, even without┬Āthinking about it.

In old Hollywood┬Āfilms┬Āthis was obvious.┬Ā

The camera moved slowly across a womanŌĆÖs body, using close-ups on her lips, legs, or chest.┬ĀBut┬Āwhat is interesting today is how this idea has┬Āmoved┬Āinto┬Ānew media┬Ālike┬ĀTikTok, Instagram, and music videos.┬ĀThe male gaze is not only something created by film directors anymore. Now, it is something people repeat┬Āthemselves┬Āonline.

Women and girls learn how to pose, take selfies, and record content with the awareness that someone is looking. The camera becomes the eyes of the viewer, and many times, the viewer┬Āis imagined┬Āas a man.┬ĀThis┬Ācreates a kind of ŌĆ£self-objectification,ŌĆØ where women start performing for the gaze before anyone even asks them to. It is part of social media culture now, and it means that the male gaze is not just in┬Āmovies┬Ā┬Āit┬Āis inside our phones and our own behaviours.

A good example to discuss is┬ĀBritney SpearsŌĆÖ ŌĆ£WomanizerŌĆØ┬Āmusic video. On the surface, the video┬Āseems like it challenges┬Āthe male gaze. Britney plays different characters, and she takes control of the cheating man. She even follows him and exposes him.┬ĀBut┬Āat the same time, the video uses classic male-gaze visuals: shiny skin, lingerie, close-ups of her body, and slow shots that highlight her sexuality. So the video is both empowering and still shaped by the same system it tries to criticise

This shows how complicated new media is. Women can be powerful, in control, and confident, but still filmed in a way that encourages the audience to look at their bodies first. Social media influencers, fitness creators, and pop stars often deal with the same contrast. Even when they take control of how they present themselves, the gaze does not disappear.

So, the male gaze today is not┬Āonly something┬Āproduced by men.┬ĀIt is repeated by society, by technology, and sometimes even by the women in the images. New media┬Āhas┬Āchanged the tools, but not always the way we look.┬ĀAnd┬Āthat is why┬Ātalking about┬Āthe male gaze still matters because it teaches us to question who is looking,┬Āand what we are┬Ābeing told┬Āto see.

References

Mulvey, Laura. ŌĆ£Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.ŌĆØ 1975.

Ross, Karen.┬ĀGendered Media: Women, Men, and Identity Politics. 2009.

I thought your post explained the idea of the male gaze in a really clear and relatable way. I liked how you showed the shift from old Hollywood films to todayŌĆÖs social media, because it makes the theory feel much more relevant to how people actually behave online. The part about women learning to pose or film themselves with an imagined viewer in mind really stood out to me, since it captures how quietly this idea works in everyday life. Your example of Britney SpearsŌĆÖ ŌĆ£WomanizerŌĆØ video was interesting too, because it shows how something can look empowering on the surface while still using visuals that come from the same system it is trying to challenge. It made me think about how complicated it is to separate confidence from performance when everything is shaped for an audience. I found your post easy to read and thoughtful, and it gave me a new way to notice how much of the male gaze is built into the way we use our phones.

I agree, and I think that the concept of self-objectification is so important to include in the discourse surrounding male gaze. It’s one thing to recognize when media has been filtered through a male gaze, but it’s an entire new issue to realize we as women have been conditioned to put ourselves in that light often. It would be interesting to have a conversation about whether this is empowering or complicit, because I could definitely see it from both sides. Are women just taking ownership and authorship of their femininity/sexuality, or are we becoming part of the problem? It also makes you think twice about the kind of media you’re producing and consuming, not just in terms of the male gaze but really everything we’ve discussed over the semester. This example highlights how easy it is for audiences to become involved in these systemic issues and the role we play in the theories we’ve explored, even when you initially think you wouldn’t fall for it. -Thalia