Fashion advertising rarely hides its intentions: it sells desire as much as it sells clothes. But Dolce & GabbanaтАЩs 2007 Spring/Summer campaign takes this formula to an extreme, offering a visual world built on power, dominance, and an unmistakably gendered hierarchy. When looking closely at the two images from this campaign, the dynamics that Laura Mulvey describes in тАЬVisual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaтАЭ become almost unavoidable. These ads do not just reflect the male gaze; they amplify its logic until it becomes impossible to ignore.

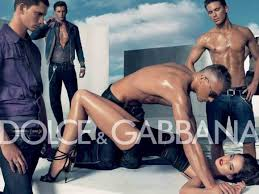

The first image is perhaps the most infamous. A woman lies pinned to the ground by a male model, her wrists restrained while four other men stand above her, observing. Their postures are relaxed, confident, even bored, with their hands in pockets, their bodies angled downward, their gazes fixed. She is the only person on the ground, her body twisted into a powerless pose. This spatial arrangement, with the men towering above and the woman immobilised below, visually encodes the very structure Mulvey identifies: woman as image, man as the bearer of the look. The men are the active agents; the camera invites the viewer to share their vantage point. The womanтАЩs body becomes a surface for both their gaze and ours.

It is no surprise that critics accused the image of glamorising sexual violence. Fashion MagazineтАЩs timeline of D&G controversies notes that this specific advertisement was interpreted by many as evoking a gang-rape scenario, prompting Spain and Italy to remove it from public display. Situating this response in a broader media context, Karen RossтАЩ analysis of gendered imagery in Gendered Media helps explain the public unease: contemporary media frequently packages sexist or hyper-masculine performances as playful, ironic, or aesthetically neutral, even when they rely on deeply entrenched gendered power dynamics. Ross argues that representations of masculinity and femininity in popular culture often disguise their ideological work behind style and humour, flattening women into objects of sexual availability while elevating men as agents of control. This is precisely what happens in the D&G campaignтАФthe visual codes appear тАЬstylised,тАЭ but the underlying logic is unmistakably patriarchal.

The second image from the same series initially seems to offer a reversal: two women stand tall in metallic dresses while a male photographer crouches below them, aiming upward. At first glance, the women appear dominant. Yet the visual strategy remains firmly embedded in male-gaze aesthetics. Their bodies are hyper-stylised, posed to emphasise legs, curves, and a posture designed for display. Even though the male figure is physically lower, the camera is still directed at the women’s bodies as commodified surfaces. This is what scholars identify as a postfeminist masquerade, a dynamic in which empowerment is coded through sexualisation. What looks like authority is still moulded inside the same visual vocabulary that treats the female body as spectacle.

When read together, the two images reveal a consistent visual logic: regardless of whether the women are pinned down or placed above a male photographer, the power of looking remains aligned with men or with the spectator, while the women remain the objects of the gaze. MulveyтАЩs idea of the тАЬthree looksтАЭ helps clarify this structure, since in the first image the viewer stands with the male figures and in the second behind the photographer, creating the same dynamic in which femininity becomes something to be desired, scrutinised, and aestheticised. What makes the D&G campaign striking is how easily it folds these gendered power relations into a luxury fantasy, masking hierarchy with glamour. As Ross and Mulvey both note, media does not simply mirror gender norms but helps construct them, and when advertisements aestheticise domination or sexualised display, they make such patterns seem normal. The campaign therefore illustrates how the male gaze continues to shape contemporary visual culture, even in images that claim to celebrate beauty or empowerment.

Reference listя╝Ъ

Fashion Magazine (2023) A comprehensive timeline of Dolce & Gabbana controversies. Available at: https://fashionmagazine.com/style/stefano-gabbana-offensive-timeline/ (Accessed: 30 November 2025).

Mulvey, L. (1975) тАШVisual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaтАЩ, Screen, 16(3), pp. 6тАУ18.

Ross, K. (2010) Gendered Media: Women, Men and Identity Politics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Such an interesting and relevant example of male gaze, especially how it’s persisted in media over time! You’d think that things would’ve changed in the nearly 20 years since these photos were published, yet I feel like I still see very similar imagery in magazines and fashion advertisement all the time. Perhaps it’s considered more cleverly disguised on the surface, like with the second image shown, but any quick analysis of the posing and characterization of the men vs. women will reveal the male gaze driving it all. It also reminds me of the adjacent conversation about “female gaze” and if it sets unrealistic expectations for men’s appearances. I honestly feel like this is also the male gaze at work, and these versions of what men should act and look like were created and upheld by men themselves. After all, as Mulvey established, women didn’t have the power to create such a phenomenon- men did. I think that while men like to counter her argument with, “There are unfair expectations of men, too”, they fail to see that male gaze created both. -Thalia

You’ve written quite meticulously, dissecting the two advertisement images thoroughly, allowing people to immediately recognize the visual logic that they previously thought was merely a style but is actually a power structure. While reading, I also recalled my own feelings when browsing advertisements or watching fashion spreads – some images initially seem “so cool” or “so beautiful”, but upon closer inspection, one realizes that this beauty is built on a very familiar gender position: men look, women are looked at. Many times, I didn’t even realize that I had been trained to take this perspective for granted. Therefore, the value of this analysis lies in the fact that it’s not just about D&G, but it reminds us that many of the images we see in our daily lives are actually repeating the same framework, just with more elaborate packaging.