Introduction: What Is the Male Gaze?

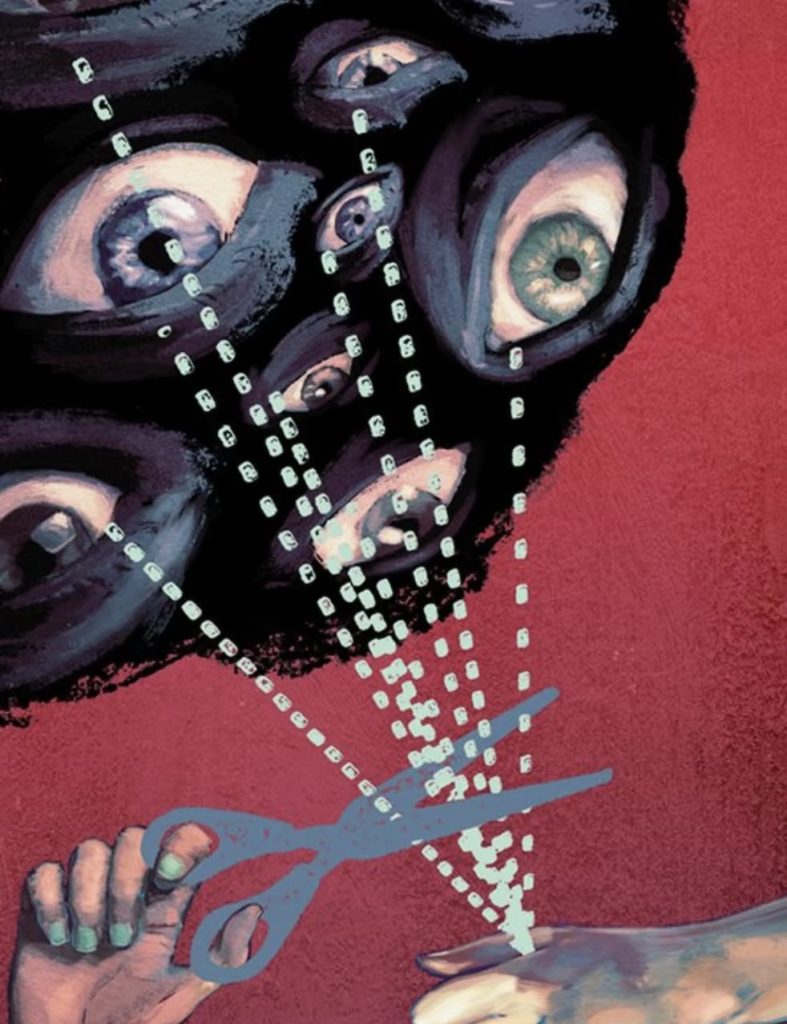

The male gaze, defined by Laura Mulvey (1975), describes how visual media positions women as objects of heterosexual male pleasure. Through camera angles, narratives, and character design, women are framed to be ŌĆ£looked at,ŌĆØ while men control action and perspective.

Media Objectification: How Women Are Framed

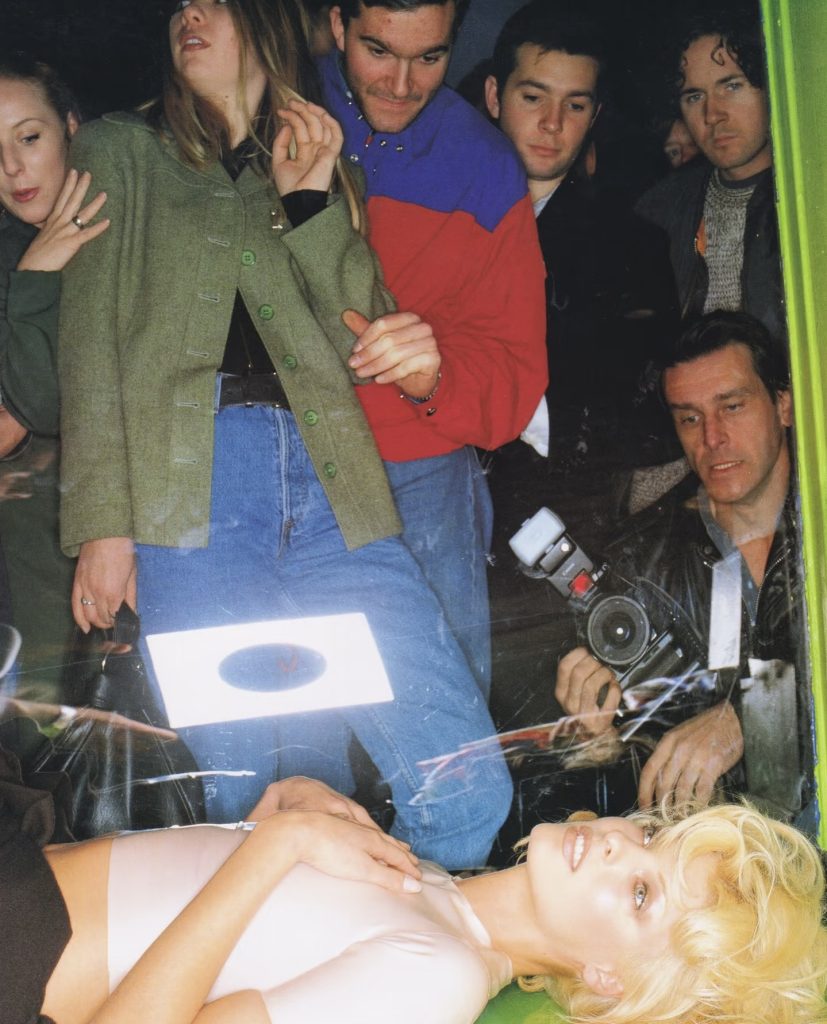

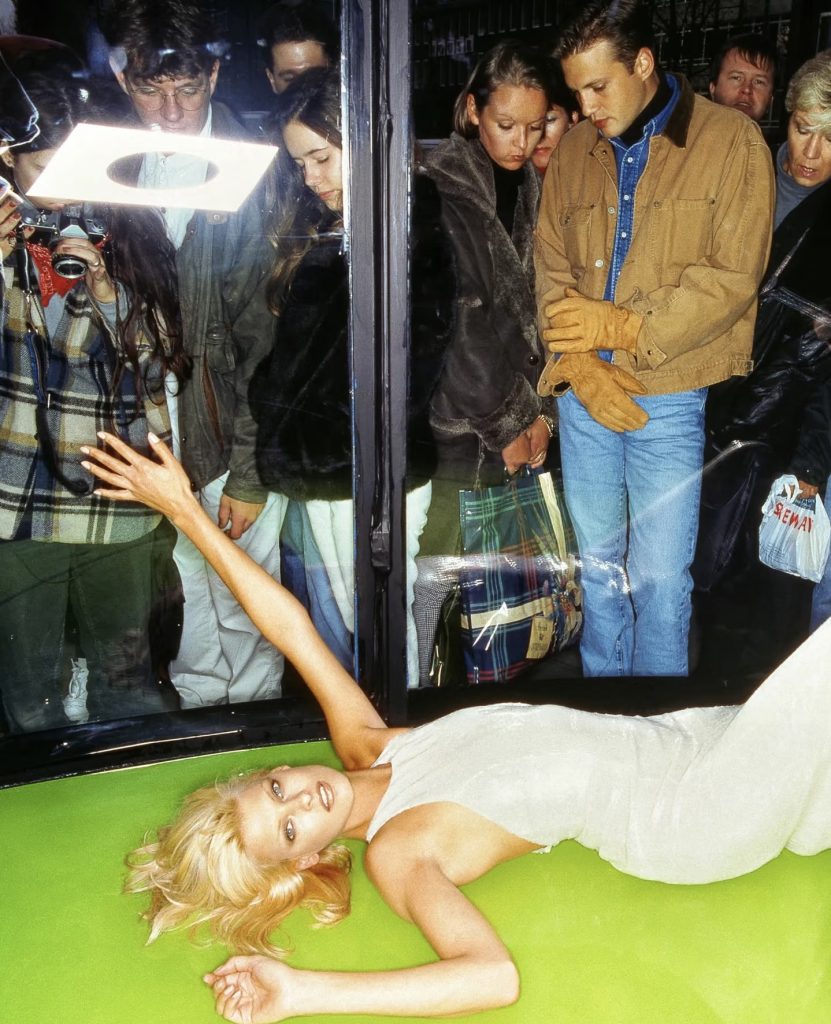

Films and advertisements frequently use fragmented shotsŌĆölegs, lips, curvesŌĆöto aestheticise the female body. This reduces women to visual commodities rather than full subjects.

Case Study: Hollywood Superhero Films

A clear example of the male gaze is Harley Quinn in Suicide Squad (2016). The camera lingers on her body, emphasising her short shorts, curves, and ŌĆ£sexy craziness,ŌĆØ prioritising visual appeal over character depth.

In contrast, Birds of Prey (2020), directed by Cathy Yan, presents Harley from a female-centered perspectiveŌĆöless sexualised, more narrative-driven. This shift shows how directorial choices reshape gender representation.

Social Media and Self-Objectification

Platforms like Instagram and TikTok reward sexualised images through likes and algorithmic visibility. As a result, women may internalise the male gaze, curating their bodies as ŌĆ£content.ŌĆØ

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Power to Look

The persistence of the male gaze is not simply a matter of how women are filmedŌĆöit reflects the deeper cultural structures that shape who is granted agency, who is allowed to speak, and who exists primarily to be seen. When films, advertisements, and social platforms repeatedly present women as visual objects, they influence far more than representation: they shape aspirations, self-worth, and the boundaries of what femininity is allowed to be.

But recognising the male gaze also opens a space for resistance. When directors reframe women as subjects, when creators refuse objectifying tropes, and when audiences learn to question how images are constructed, the act of looking becomes political. It becomes a form of reclamationŌĆöa rewriting of who gets to occupy space, who gets to be complex, and who gets to be more than a spectacle.

To challenge the male gaze is ultimately to imagine a media world where women are not reduced to bodies, but acknowledged as full human beings. And that shift does not only change screensŌĆöit changes society.

Reference List

Mulvey, L. (1975) ŌĆśVisual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaŌĆÖ, Screen, 16(3), pp. 6ŌĆō18.

Gill, R. (2008) ŌĆśEmpowerment/Sexism: Figuring Female Sexual Agency in Contemporary AdvertisingŌĆÖ, Feminism & Psychology, 18(1), pp. 35ŌĆō60.

Rose, G. (2016) Visual Methodologies. London: Sage.

McGowan, T. (2015) The Real Gaze: Film Theory After Lacan. State University of New York Press.

This blog offers a concise yet compelling critique of the male gaze, framing it not as a superficial visual issue but a reflection of entrenched cultural power structures that circumscribe female agency and identity. By linking media representation to real-world impacts on aspirations and self-worth, it underscores the far-reaching stakes of visual objectification.

More importantly, it pivots to a hopeful narrative of resistance, highlighting how directors, creators and audiences can transform “looking” into a political act of reclamation. The call for a media landscape centering womenŌĆÖs full humanity as opposed to their bodies is both urgent and timely, serving as a potent reminder that shifting visual narratives is foundational to societal change.