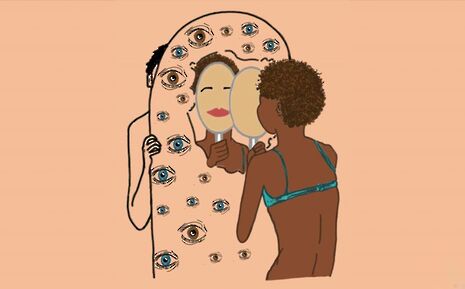

Since its first publication in 1975, Laura Mulvey’s theorization of the male gaze has remained a central framework for making sense of the gendered dynamics of looking in visual media. Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema argues that mainstream film constructs women as the passive objects of heterosexual male desire, while men occupy the position both as active spectators and agents within narrative structures. It does this through three interrelated forms of looking. These include the gaze of the camera, the gaze of characters within the diegesis, and the gaze of the audience which work together to naturalize a visual regime built around male pleasure and places femininity as spectacle.

The significance of Mulvey’s model comes from the fact that its relevance stretches far beyond classical Hollywood cinema from earlier years. This is due to the fact that, contemporary visual culture, via advertising, gaming, and social media, is still informed by tropes associated with the male gaze. This is because fragmented depictions of female bodies, hypersexualized images, and storylines valuing appearance over agency is still a common practice in modern media. Their persistence suggests that ideological mechanisms identified by Mulvey function within today’s environment of rapid image circulation and commodification.

Nevertheless, the theory has received significant criticism. Scholars such as bell hooks (1992) counter Mulvey’s universalizing schema with considerations of race within the field of spectatorship. Hooks’ oppositional gaze suggests that Black female spectators reject and re-signify dominant visual codes; thus, this disrupts Mulvey’s binary division between viewer and viewed. More recent formulations of the female gaze and queer gaze further emphasize possibilities of marginalized artists to subvert dominant visual orders. Such ideas underpin the role of authorship and social context in contributing to meaning. This extends its interpretive potential by placing the male gaze within broader structures of power.

Most points have been reflecting on these debates in the context of my own creative practice. In producing a short video project, I found myself unconsciously adopting and reproducing visual conventions of the male gaze, for example in the reliance on close-ups, which framed a female character primarily through her physical features. Going through Mulvey’s views has inspired me to redo those decisions and correct them. When changing the direction and production of the work to focus more closely on the character’s point of view and inner life, the result of the project turned away from common objectification and towards a more ethically grounded and narratively rich representation. Current filmmakers like C├®line Sciamma and Chlo├® Zhao continue to show effective ways in which unique modes of filming can test the dominance of the male gaze. Their focus on the subjectivity, interiority, and relationality of their media shows proof that media can resist the structural patterns that Mulvey identifies.

In short, the male gaze is still a valid intervention into the analysis of the persistence of gendered power in media. Its worth lies not only in its explanatory potential but in its value as an incitement to further critical engagement.

References

hooks, b. (1992) Black Looks: Race and Representation

Mulvey, L. (1975) ŌĆśVisual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaŌĆÖ, Screen, 16(3)

Sciamma, C. (Director) (2019) Portrait of a Lady on Fire [Film]

Zhao, C. (Director) (2020) Nomadland [Film]

I really enjoyed reading your post because you explain MulveyŌĆÖs ideas in a way that makes their relevance today feel very clear. I especially liked how you connected the theory to your own project. The moment you mentioned catching yourself using those close-ups felt very real, because it shows how easily the male gaze slips into our work without us even noticing. Your decision to rework the scenes from the characterŌĆÖs point of view was a great example of how theory can genuinely change creative practice instead of just sitting on the page. I also appreciated that you brought in hooks and the idea of alternative gazes, since it reminds us that Mulvey isnŌĆÖt the whole story and that different viewers and creators bring their own positions to the frame. The examples of Sciamma and Zhao worked really well too, because they show what resisting dominant visual habits can actually look like in practice. your reflection feels thoughtful and grounded, and it made me think more carefully about how much of what we consider ŌĆ£normalŌĆØ in film language is actually shaped by long-standing power structures.

This blog illustrates the Male Gaze concept/theory for us from a panoramic view. The author introduces how and when this theory was published, and also explains why this theory is still meaningful and worth our attention. Because even in recent times, those forms of entertainment content still have problems when it comes to addressing gender equality, and many pieces of media content or artworks still cannot fully avoid being filmed or depicted from a maleŌĆÖs perspective.

Besides, the author also shares his/her own reflection on this topic. Artworks need to break free from the stereotypes and habitual patterns that have long been ingrained.